My Father never really cared for me when I was a child. I was not so much the bane of his existence, rather a mild annoyance. There was a glaze across his eyes that no amount of my noise or silence could remove. But even as a boy, I always fancied that I would win him over one day.

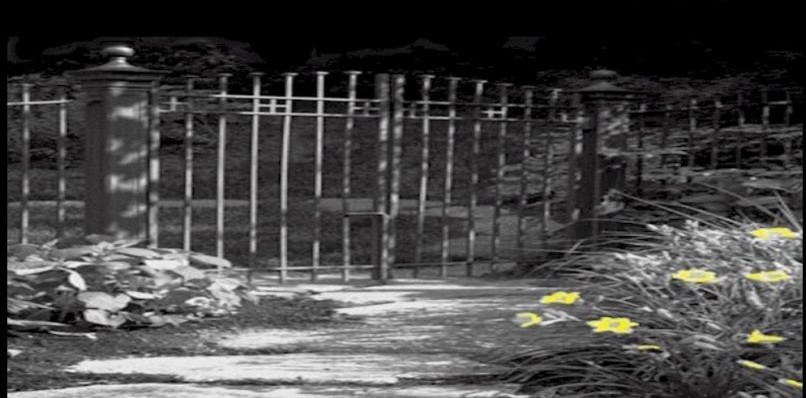

We lived alone in a grand (albeit partially dilapidated) house surrounded by thick, dark woodland. It was in this woodland that I found myself wandering by myself for hours at a time, in all weather, learning how to distinguish bird calls and navigate the landscape using the trees. I knew almost every inch of the place by the time I was a man.

It was on one of my daily wanderings that I stumbled across the skull in the undergrowth. I had never seen anything quite like it. It was too large to have belonged to any creature I had ever encountered in the woods before. It lay amongst the ferns, half-buried and I fancied that it must have been exposed by the heavy rain that had turned the ditches to ponds and battered against my windows during the night.

I wiped the wet dirt from it with my fingers, admiring the way the dim light caught its surface. There were no discernible cracks, and all the teeth seemed to be accounted for. The teeth were quite long, too. Sharp. Something akin to fangs if I had to describe them more clearly. Whatever creature the skull belonged to must have been rather large.

Having been unable to locate the skeleton it belonged to, I decided to take the thing back with me. It was cold in my hands, and left smudges of dirt on my sleeves.

I filled the kitchen sink with warm water and cleaned the remaining dirt from the creases with a toothbrush. Tiny bubbles formed tinier patterns and rainbows glimmered in each of them. I was mesmerised by the way the dirt clouded the water like pipe smoke before turning the entire pool dark.

I decided to gift the skull to my father in a pale cloth and the glaze that had sealed his eyes from the world for all the time I had known him vanished almost instantly. He stared at it and gazed deeply into the seemingly empty eye sockets as though it were the face of a beloved pet.

He looked to me and smiled. For the first time in our lives, he smiled at me. I had caused the joyful expression on his face, merely by bringing this object to him. However, after a month or so, his demeanour changed again, and I sensed he was slowly reverting back into his old self. I reasoned that I would have to repeat the act of the gift in order to maintain our relationship.

***

The second prize I managed to obtain was the result of an accident. I startled Croydon at the edge of a small crag and seized the opportunity with both hands. Though this was also how I learned to be more observant, more patient. For Croydon’s teeth were not all that beautiful. Father appreciated the gift, of course, but his merry mood did not last as long as it had when he set eyes upon the first one, whom I had dubbed ‘London’.

I decided that I would have to be more discerning in future.

I named all the prizes according to the towns or cities I imagined them to have been born in. There was no real logic to their assigned monikers, just something I fancied they looked like they would suit. In fact, I found myself constructing elaborate backstories for them to pass the time as I watched them. However, if they were unsuccessful at passing the mirror test, I would revoke their name and abandon their back story altogether.

The mirror test was an admittedly childish, nonetheless effective game I had devised to determine whether a prize was worth apprehending or not. I had become quite adept at catching rays of light on a small pocket mirror and reflecting them into the prize’s eyes (with varying degrees of difficulty, depending on the target’s vigilance). On occasion, they would become spooked by the sudden glare, and speed up their journey. This proved somewhat useful at times, as they would shout into the trees, inquiring as to who was there and such, which afforded me an even better view of their open mouths. Other times, it proved most disruptive to my operation, as I would have to be ever more cautious when initiating contact, what with them already anticipating my approach.

My ever-discerning eye allowed me to gain the highest praise from Father, who showed his appreciation for my diligence and perseverance in the form of warm affection. The likes of which I believed was long overdue.

As the years went by, I was able to form a tight bond with my father, and I could confidently claim that he had grown rather fond of me in the time since I had happened across the first of the prizes. London took pride of place in Father’s room atop the mantlepiece, resting on a little purple cushion, encased in a small glass cabinet.

The others were originally confined to the box room, which also featured a large map that I marked places off of according to their corresponding prize counterpart. But soon the collection grew too large for just one room, and we were forced to spread it out around various other places throughout the house. This provided something rather personal, I felt. The prizes were more like a part of the family if they were scattered about the home, rather than a mere collection of items stored away like bric-a-brac.

***

Father soon grew sick with age, and I resolved to present him with a prize more regularly, to keep him in good spirits. This presented difficulties, of course, namely the low number of prizes in the woods in the first place, and the need to find prizes of continuous good quality. I managed to provide my father with a steady supply of decent prizes until I happened across the very last one my father would see – Richmond.

The last proved the most difficult to procure by far. I had watched and tracked Richmond for hours in the blistering summer heat, all the while feeling myself becoming more and more like my father as I admired the teeth in the still living skull. They were perfect. Straight, clean, without any visible stains.

At one point, Richmond stopped to rest, and I was almost certain that I had been spotted or that my very presence had been sensed. I crouched in the ferns and lay on my belly amongst the leaf litter, listening as tiny souls skittered about in the foliage.

I took advantage of the stillness and seized the opportunity to administer the mirror test, just so I could see the teeth in their natural environment. Richmond held up a hand to shield against the light and exposed the teeth. I knew then that they truly were the finest yet.

I found myself wondering if in harvesting this prize I would be depriving the world of a marvel, a wonder. But I reasoned that if anyone deserved a gift meant for all the world, it was my dear father, whose company had given me so much purpose over the last few years.

Richmond proved a reluctant contributor to the prizes. The altercation that ensued upon my initiation of physical contact was rather messy, and at one point I feared that I might have damaged one of the front teeth. Had that been the case, I would likely have descended into insanity there and then, such would the effect a loss of that calibre have had on me.

Fortunately, the only real damage Richmond sustained was a small crack at the back, which would be completely unnoticeable when displayed, given that the teeth were the main feature.

***

I gently caressed the ghostly white in the darkened water, removing all traces of crimson from the bone. I dried it with a cloth and, as usual, left the teeth for last. I polished them with a softer brush than I would use for the rest of the skull, mindful not to loosen any. My fear was not entirely unfounded, considering the scare I had when I initially obtained it.

I climbed the steps to Father’s chamber, carrying the skull in a black cotton cloth, so that it might enhance the gleaming whiteness of the bone.

Father was propped up in bed, eyes half open.

I crept across the room and told him in a whisper that I had yet another gift. His eyes opened fully, and he smiled as I unfolded the cloth and introduced him to Richmond. He chuckled, a wheezing, stunted chuckle that I had never heard him produce before.

I moved Richmond closer to him and he took the prize in his crooked hands. His watery eyes grew wide and glinted in the candlelight and for the final time he looked at me and smiled, before uttering the last words I would ever hear him speak:

“Such beautiful teeth.”

Jakob Angerer is a writer from the Wirral, UK.

Published 6/5/25