Despite time’s passage, still I remember the final argument I shared with that most lovely maiden, whom I had hoped might someday be my bride. The year was 1871, nearly a decade ago, and yet the entire dismal affair is as crystal clear to me as the glass of cold water upon my cluttered desk.

I shall be evermore eternally haunted by that startling gaze when she heard my parting words, that unfortunate and careless accusatory remark, the last words she would ever hear me utter, in what I now recognize as my utter and complete ignorance.

Maracill was a slender and languid brunette with hair most long, and, dare I say, even longer legs. To say she was beautiful may be even worse than understatement; such inadequacy to describe her glory almost does her a disservice. She was, quite simply, the most striking young lady my eyes have ever beheld.

We met by moonlight in a botanical garden, where she appeared fascinated by large statuary representing reptilian behemoths long extinct. I myself was experimenting with technique and formulae by which one might utilize photographic equipment in minimal lighting. This too intrigued my curious observer. Sometime later after I had developed the films, I returned to the garden. One image featured this fair stately maiden. The lady feigned shock and amusement that her pale visage had so been captured as it were by the silver nitrate. I carelessly remarked her billowing and embarrassingly sheer gauze dress looked rather like a tattered funerary shroud in the moonlight, given that all features were blurred. Her odd reaction was to glare icily at me, only to erupt in raucous laughter upon my blush.

Before long, our casual outings took on the tone, if not content, of courting. Once she realized this, she took pains to inform me a romance was not her intention. Her demand was inscrutable, to which I countered that we clearly desired the other’s presence beyond mere formal discourse, which the lady could scarce deny. Yet did she insist I would encounter only bitter disappointment were I to pursue her amorously. When pressed, she would confess only that it had been ages since she last entertained a male suitor, in her words, which I took to imply an asocial celibacy. She did indicate she was fond of me, because of and not despite, my admittedly less than robust physique and my too-fine features. She concluded with assertions that even were she to feel enamored, she was not in a condition for a paramour, after some recent negative experiences. I acquiesced, because her behavioral attitude was occasionally at odds with these proclamations, which gave me hope.

To my relief she did not avoid my companionship, indeed her actions often belied her stated non-intent. Maracill could display true affection in precious fleeting moments, catch herself, and whisper gentle reminders prohibiting adoration. Unsurprisingly, I was not so easily dissuaded by these limitations. To my joy and eternal gratitude, she gradually relented over time. I witnessed her chilly demeanor melt into playful mirth, if not warmth. At risk of sounding less than gentlemanly, I was eventually rewarded one stormy evening with a tentative kiss by her cool and very soft lips. I was thereafter lost.

The chilly evenings rapidly passed as I grew ever closer to my shy and gentle young eidolon. And yet the reticent lady remained obstinately mysterious. Initially that enigmatic nature held a forbidden appeal to me quite undeniable. However, a looming calendar date would soon overtake my devoted patience. Maracill had rarely, if ever, inquired about my own unstated history, and so it had transpired I myself had omitted a rather crucial detail. Whether out of cowardice or reciprocal subterfuge, I had not yet informed the lady Maracill that despite my youthful inexperience and immaturity at the tender age of eighteen, I was newly in possession of two young children, a boy and a girl.

These darling twins were not of my own production, but those of my poor late sister. Technically, therefore, my niece and nephew. The dear woman had passed away during an outbreak of cholera the year before, preceded by her husband, which was not unlike the tragedy that had plagued our region some years back when several young women had died of consumption. On her very deathbed, my elder sister had procured my solemn vow to raise and protect those tiny treasures, a promise I upheld as both sacred duty and tremendous honor. The inquisitive children were away on extended winter holiday, mere weeks from return. I would soon need to acquire sufficient courage to inform Maracill of their existence. How such a potent revelation might be received was far from predictable.

In my starry-eyed foolishness, I had somehow neglected to notice Maracill’s frequent strange behaviors and inexplicable aversions. She did not appear to be engaged in any study or meaningful activity, and adamantly refused to bother awakening before late afternoon. We often contested this matter of perceived sloth, to her not insubstantial irritation. She despised any religious references and paraphernalia whatsoever, which precluded any possibility of introducing my devout parents, or even my mildly spiritual sister. Our first major argument revolved around such an issue, when I rather innocuously proffered a gift of a golden cross on a silver necklace, a rather impressive Celtic cross at that. Her unexpected and offensive response was to fling the costly present into the nearest stream without explanation or apology.

Even so, I was determined to win her over, so devoted to her attentions was I. I bore all manner of degradation when the young lady was in a mood, and innocently deferred to her good graces. I often faced insurmountable and thoroughly baffling difficulties with Maracill’s quirks, oftentimes exhibited at the most inopportune moments. Pitifully, I would continue to reckon my days by every eagerly awaited rendezvous.

The final straw, as they say, occurred the evening I clumsily lacerated my arm whilst preparing a bouquet of yellow roses for my dear ailing mother. Despite her age, she had rarely fallen ill, and I was particularly concerned, and therefore, distracted. I attempted to staunch the blood flow with my left hand in the interim, fully anticipating Maracill’s much-needed ministrations to patch and bandage my not insignificant wound, to say nothing of cleaning the resultant mess to complete the bouquet. However, far from tending to my injury, the lady stared wide-eyed at it for an instant, before she leapt backwards and departed the scene. Ordinarily I might sympathize with a woman’s natural squeamishness, but she neither returned nor sent help. Quite naturally, I was livid.

Much later in the evening, I eventually spotted my deserter in the yard through a window, standing stiffly and forlornly looking upon my flat. I rushed outside in panic and anger, perhaps even fueled by lingering pain. I shouted at her as she remained immobile and silent. I reviewed the bloody incident for her consideration and asked if she would have me die. Maracill’s cold but earnest reply was that no, she would not have me die, that she would in fact have me live, which is why she must forever depart. She further intimated that my health and livelihood would be better served by her immediate absence, a remark I found most curious and appalling.

Needless to say, this was a most devastating revelation, delivered at the worst possible moment. Here I sought understanding and sympathy, yet evidently, I was to receive only complete abandonment. Very nearly in tears and in haste, I yelled at my young lady, stating that surely she must be an incredibly evil and insensitive monster to be so cruel and heartless. I fully anticipated aggrieved reproach or some similar manner of emotional response. I could not have expected, nor ever imagined, the incomprehensible reaction I ultimately received.

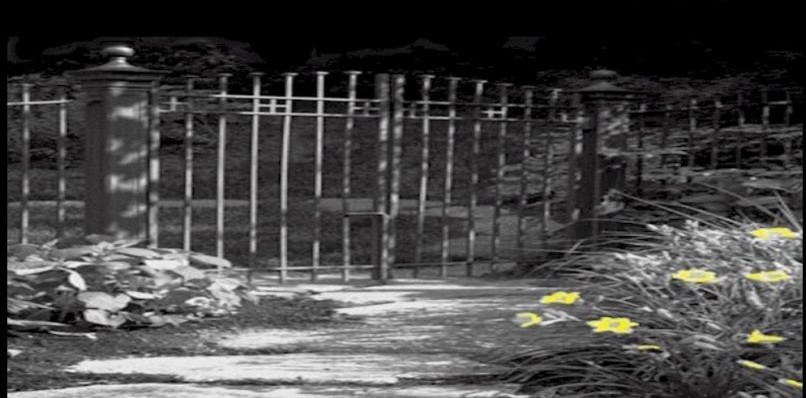

Maracill had lunged at me, and actually snarled, as a great feline might. She bared her teeth at me, which to my horror, had visibly and strikingly grown into long fangs before my very eyes. Her once lustrous and luminous eyes flashed bloody red, and I involuntarily drew back with a less than brave shriek. Yet, beneath those terrifying burning eyes, a single tear rolled down her pale cheek. And then she was gone. The woman had leaped over the tall gates instantly in one fluid motion, a magnificent and frightful feat impossible even for an Olympian.

In that moment, everything finally became clear to me. I found myself succumbing to alternating and conflicting feelings of sorrow and relief. As well as abject terror. Even so, all of the trysts and conflicts of the preceding weeks suddenly seemed somehow completely ludicrous. I also discovered that my newfound accidental knowledge of my beloved lady’s terrifying secret and true nature did not abate my deep feelings for her.

Maracill was gone. I remain, nearly a decade removed from the nightmare, tormented by that concluding chapter of our misadventures. I subsequently wasted two years of my life futilely searching for her. I am absolutely certain I shall never meet anyone quite like her. I find I do love her still, and ever shall for the rest of my days. Occasionally I even fancy I hear her light step in my darkened halls. My lady haunts my dreams. Yet never again did my eyes behold my dear vampiric Maracill.

P. S. Traum is an author with a range of styles who has had short stories published in several small press genre publications. PST has had more than three dozen short stories published since 2020. Forthcoming for publication is a collection of short stories. Traum eschews publicity in the hopes the storylines and characters get all the attention without preconceived perceptions of external context.

Published 2/15/24