Zurn moved through the labyrinthine corridors of the souk with a searching gait. The mosquito nets draped across the stalls offered paltry protection from the red burn of the noonday sun.

But Zurn ignored the rising temperature. Her eyes seared through the waving hands, the indigo and saffron dyed textiles, the endless rows of gold-flaked tin goods.

Much like her father before her, Zurn lived ruthlessly, directed only by the pull of adrenaline.

It yanked her down the chattering wet markets and cluttered red-light districts of Manaus, Bucharest, and Phuket.

Not that her boredom with these places ever subsided. All things gathered under the shadow of her father who had disappeared years ago withered into anecdotal irrelevance.

So far, the souk in the Amber Quarter was no different. He had written about its existence in his diaries. But as Zurn stepped on a patch of worn cobblestones, so contoured by the boot-clad feet of a man who was no longer there, her hopes that she would reach some sort of breakthrough for herself were waning.

Suddenly, an arachnid motion darting along one of the walls made Zurn stop and turn her head.

A stall, no wider than a child’s desk appeared before her. The counter wood was carelessly brushed in streaks of talcum blue.

On it, there were three large ceramic pots, and a clapboard sign propped up by a glass jar which proclaimed “spider game” in a black swirling scrawl.

The gamekeeper, a man in a white linen shirt with a heavily lined face and protruding cheekbones, nodded at her.

“What’s the game?” she asked tersely in the local tongue.

“Come and see,” the gamekeeper responded in English. A wide grin cracked the leather-like skin around his mouth, revealing rows of filed-down teeth.

Zurn stepped in closer. She couldn’t recall this from her father’s diaries, “I’m looking for something special.”

The gamekeeper clapped his thin hands together in delight, “This will not disappoint!”

He moved to the side to lift the glass jar propping the sign up.

While he did, Zurn investigated the pots.

Their insides were polished black so deep that the dappled rays of light filtering in through the reeds appeared to get sucked in. A faint breeze ululated mournfully above the lip of the pots.

She barely noticed the man when he shook the glass jar in front of Zurn’s face.

“One dirham buys you three tries with this rare import,” the gamekeeper said, placing it in her sweating hands.

Zurn squinted and investigated the jar.

Among a thick weave of white funneled webs, she saw it, rearing its dripping fangs in anger.

Zurn shuddered, giving it back, “Three tries to what?” Zurn asked. The thing was hideous; a Jurassic remnant that should have gone extinct with the asteroid that took the dinosaurs.

“To play of course,” the gamekeeper smiled, “But be warned. The spider always wins.”

Zurn raised her eyebrow, willing to bait those odds, “Alright, here’s your dirham, old man. Let’s play.”

The gamekeeper unscrewed the jar. Zurn watched with disgust as the eight-legged shadow within escaped into the pot furthest to the left.

The gamekeeper winked and shuffled the pots. Zurn tried to keep her eyes pinned on the one she thought the spider had jumped into. But he moved them with practiced dexterity, until she lost track of which pot contained the spider.

Then, the gamekeeper stopped and motioned downwards, “Please.”

“Are you serious?” she asked.

The gamekeeper nodded.

A cold bead of sweat formed on Zurn’s neck.

“Until you touch the bottom, please,” the gamekeeper said.

Her heart thumped in her chest. Certain that the center pot was empty, she stuck her hand in. When she finally touched the base, it felt like she had inserted her whole self into the pot.

Zurn waited for the fangs to pierce some part of her flesh. But no bite ever came.

“Very good!” the gamekeeper said, impressed.

Blood pumping in her ears, Zurn felt euphoric, as if she’d drank a strong cup of coca tea, “I found my own, old man,” she whispered.

The gamekeeper knotted his eyebrows, “What did you find?”

Zurn shook her head, “Something that my father never touched.”

Indifferent, the gamekeeper tapped the lip of a pot, “You will try again, please.”

Zurn swallowed. She watched as the gamekeeper shuffled. Almost imperceptibly, a black blot darted from pot to pot. She picked one, this time the one on the far left. The gamekeeper nodded.

Zurn held her breath and stuck her hand in. Once more, she emerged unscathed.

“Fantastic!” The gamekeeper said, with equal parts amusement and amazement.

Zurn looked at her unblemished hand and began to believe in her own luck. Perhaps, she thought, there is no spider.

Confident, Zurn paid for several dozen rounds, overjoyed to feel something more intense than any orgasm, drug, or far-flung destination her father had ever written about or she herself had experienced. The game was exactly what she’d been looking for all these years.

Her own little creature.

But after a few hours, the gamekeeper looked around annoyed, “It’s time to rest. The streetlamps are already lit and home is far.”

“Nonsense,” Zurn snarled, “I paid. Let me play,” she reached into the pot.

Then, Zurn grew quiet. Something had changed.

A tar-like wetness that hadn’t been there before wrapped itself around her arm and pulled her deeper past the bottom, into a gummy pit. This time, her eyes felt heavy and her mind clouded, as if she’d taken a strong hit of opium.

Thinking she’d been bitten, Zurn jerked her hand back with as much effort as she could muster. The violence of the movement knocked over the pot, cracking it on the side.

They stood there for several minutes in awkward silence, until the gamekeeper looked at her with narrowed eyes, “You broke its home.”

Zurn, confused, took a step back.

The gamekeeper asked with restrained frustration, “Would you like to play one last time to pay for this cracked pot?”

Zurn, suddenly overwhelmed with exhaustion, shook her head.

“But how will you settle this, madam?” the gamekeeper pushed.

Zurn didn’t respond. Turning on her heel, she ran, stumbling like a stray shadow on the purple curtains of dusk which had settled over the souk.

Late into the night, the symptoms worsened.

Her heart galloped arrhythmically like a wounded horse. Her chest felt as if a funnel wrapped itself tightly around her lungs.

Zurn examined her white hand. There were no bruises, no puncture wounds, no indication that the spider had bitten her.

Suddenly, Zurn heard something. It was a faint, scratching sound coming from the other side of the hallway door.

But too exhausted to go investigate, Zurn turned her head and surrendered to pestilent dreams dragging cracking egg sacks.

The following morning Zurn fished through her suitcase and found one of her father’s notebooks. She read through it with desperation, but there was no mention of the spider game.

Paler than usual, eyes ringed red from lack of sleep, hands shaking from an incongruous cold that came from something lodged deep within her gut, she retraced her steps through the souk until she arrived where she thought she’d left the man who ran the spider game.

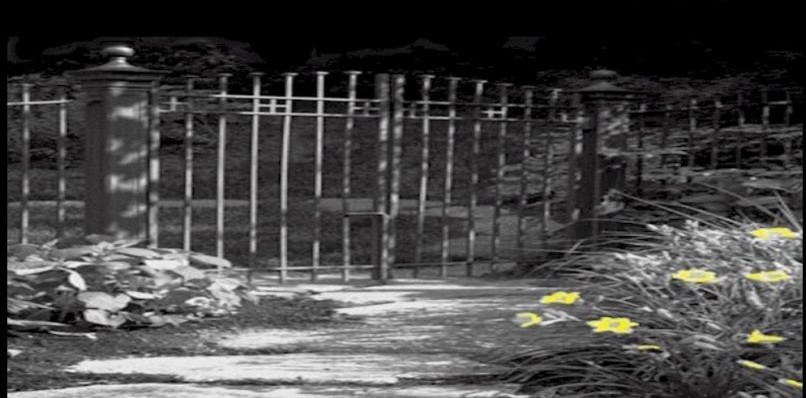

But the talcum blue stall, the pots, all of it, was gone. The space was filled with black mountains of trash bags overrun by feral cats covered in mange fighting over the rotting carcass of a mourning dove.

Zurn stood dumbfounded and scratched her itching hand. What did the man do to me? she thought.

She stumbled back to her hotel room and collapsed on her bed.

When Zurn awoke, it was dark outside.

Facedown on the sweat-soaked linen sheets, her teeth chattered, and her limbs felt stiff, possibly from the twisted angles she had fallen asleep in.

Her skin burned, as if multitudes of tiny insects with sticky, filamented legs crawled all over her.

She tried to move to scratch herself. But her arms were curled in at her hips, like stiff handles. Somehow, her legs had folded under her stomach. No part of her could move, but all of her ached.

With wide eyes she looked around.

Outside, the palm trees moved in the breeze, scraping the blue, wrought iron volutes welded against the high-arching windows. They cast a quivering web of shadows against the mosaic tiles of the patio.

Her heart pumped blood into her ears and her breath quickened. The rest of her body continued to fail.

Suddenly, a hard knock came on the door, “Housekeeping.”

Zurn’s eyes grew wider, the maid. She opened her mouth as far as it could go, but her plea for help got stuck in her throat.

The knock came again, shyer this time, “Hello?”

Once again, Zurn tried to scream.

All that came out was a faint sound akin to that of the wind blowing on the top of an empty beer bottle.

Zurn then realized her jaw was locked. Try as she might, her mouth wouldn’t shut.

Her eyes looked down at the thin line of yellow light at the bottom of the door. “I’ll come back tomorrow,” the maid said, and Zurn watched in anguish as the shadowy footsteps retreated down the hallway, clunking with their limp.

She continued to focus on the sliver of yellow light, hoping the maid would return.

Zurn dozed off briefly. When she opened her eyes, a black smudge blotted much of the hallway light.

For a moment, she wasn’t sure if she’d crossed the border between wakefulness or sleep.

All she knew was that her inability to move had gotten worse. Mouth still agape, she could no longer blink.

The smudge seeped into her room and rose around her, swallowing the moonlight and remaining slivers of yellow hallway light.

Except for a sudden pressure on her back, absence became absolute.

“It is best when you lie still, madam. It is important for you to touch the bottom,” came a hoarse whisper in her ear.

Paralyzed, Zurn tried with every remaining ounce of strength left to shake whatever it was off her, to make some sort of noise. But all that came out was a strained uuuguuu.

“If you could stop struggling, please,” suddenly Zurn recognized the voice.

It was the gamekeeper.

She tried once more to push him off her. But Zurn was trapped in her contorted flesh.

The gamekeeper placed a glass jar next to her face. Zurn stared powerlessly as he unscrewed the lid.

She watched as it dragged its heavy, polished abdomen across the sweat-stained sheets on thin, jointed legs. While it moved with difficulty, it did so with decisiveness towards Zurn’s mouth.

And for a moment, they stared at each other.

There, in the absorbing endlessness of its eight malicious eyes, she recognized her father’s steely gaze.

Zurn’s eyes strained in terror. The spider reared itself up on its hind legs. Zurn tried to command her jaw to close, nothing worked. The spider leapt into the back of her throat and sunk its angry fangs into her pink windpipe.

When her eyes opened for a final time, she could see the burning end of the gamekeeper’s cigarette. He moved his right leg up and down as the darkness spun.

She’d been placed on a potter’s wheel. The quicker the wheel spun, the more Zurn hollowed out, her insides strained into a place beyond dreams and death.

With thick, blistered fingers, he molded her breaking flesh. With care he picked out her bones and teeth. He bent her sinew and muscle into a damp home for a darting creature.

“Family reunions. Always so touching,” he took a drag and paused, admiring his work as he placed it on the shelf. Then he took a step and pressed his ear to the pot.

Inside, he could hear it, scraping through the last remaining bits of Zurn’s entrails. Smiling, he took the cigarette out of his mouth and flicked it onto the floor.

“As I said before,” he paused, crushing the last dying ember under his sandal, “The spider always wins.”

Alex McAnarney Castro (A.M. Castro) is a human rights activist by day and a writer whenever she can be. Raised in Mexico and El Salvador, she’s worked extensively across Latin America and the United States. Her fiction explores how memory, trauma, and geography often shape and twist communities, families, and individuals.

She studied journalism, literature, and creative writing at Florida International University and received a Master’s in Latin American Studies at the University of Chicago, with a focus on Medical Anthropology. Her non-fiction has been published in outlets like Truthout, OpenDemocracy, El País, El Faro, CounterPunch, UpsideDownWorld; and her short stories and poetry in Defunkt Literary Magazine, Odessa Collective, Last Girls Club, Latin@ Literatures, LatineLit Magazine, A Sufferer’s Digest, Lowlife Press, and Trinity College’s New Square Literary Magazine.

Currently, she lives in Baton Rouge, Louisiana where she spends her free time protecting her dog and husband from mutant gators with her Mongolian horse bow.

Published 6/5/25